As a young boy sweeping floors in his father’s restaurant, Vin Di Bona had little idea that one day he would revolutionize reality TV. But that is exactly what happened.

His America’s Funniest Home Videos has been airing on ABC for 25 years. It will return to the air October 11 for a 26h, making it the network’s longest-running show. The program — which he has executive-produced since its debut as a special in November 1989 with host Bob Saget — has become a television institution, known for the humorous videos shot and submitted by viewers.

In 2009 the Smithsonian Institution selected America’s Funniest Home Videos for inclusion in its permanent entertainment collections. The items on display include the camcorder used to tape the first winning home video in 1989, a cassette of home videos Di Bona used to sell the show to ABC, a ticket to the taping of the pilot and a script from that first episode.

Di Bona was born far from Hollywood, in Cranston, Rhode Island, where his family ran the town’s well-known restaurant, Lindy’s.

“A lot of my uncles, aunts and cousins worked at the restaurant,” Di Bona says. “I was a terrible cook. I was thrown out of the kitchen many times. But I could take cash when I was 10, so I was on the cash register sometimes, helping my mom out. I became a waiter when I was 14. I sang in the lounge when I was 15.”

His ambition to perform would be short-lived, but his interest in the entertainment industry would grow. By the time he was in college, Di Bona was intent on working as a television producer.

In 1981 he scored his first producing gig when he was hired on a new show called Entertainment Tonight, another series that is still around today.

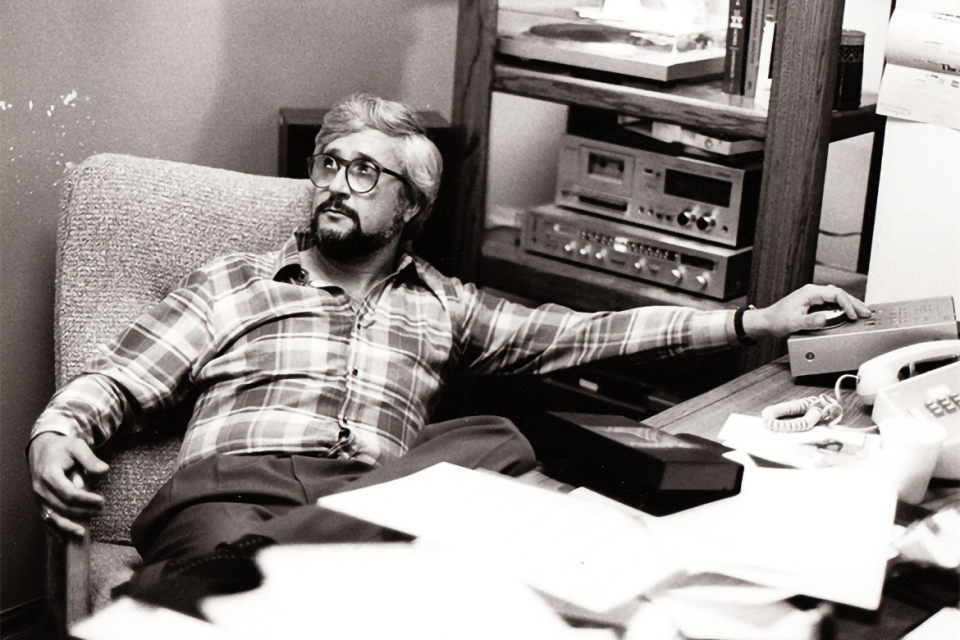

Di Bona was interviewed in January 2015 by Jenni Matz for the Television Academy Foundation’s Archive of American Television. An edited excerpt of that discussion follows; to view the entire interview, please visit TelevisionAcademy.com/archive.

Q: When you were young, you created a singing alter ego….

A: His name was Johnny Lindy, sometimes still is. I had been in the performing arts since I was eight years old. I think my mother wanted to be on stage, and she had a flair for understanding what was good.

We would go to Blinstrub’s nightclub when I was 14 or 15, and we’d see every major act that came to New England. I appeared in summer stock in Warwick Musical Theatre — as a singer-dancer and also worked as a stagehand — on shows such as High Button Shoes with Zero Mostel and Annie Get Your Gun with Ginger Rogers.

Q: Had you been given voice lessons?

A: I started when I was eight with the Walker Dramateers. Mrs. Walker would teach both adults and kids who wanted to be in television or on stage. We had elocution lessons, drama lessons and etiquette lessons, all wrapped up in one.

She had a really great conduit for us on Saturday mornings, a show that ran on WPAW radio in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. This was in 1952, and we did our own sound effects with coconuts for horse hoofs and all of that.

I started deejaying when I was a freshman at Emerson College. Emerson was a really good school for me because — I didn’t know it then — the philosophy about Emerson was, if you're a street fighter and you don’t take no for an answer you’re probably going to work out.

Q: One of your fraternity brothers went on to become famous….

A: There was this guy, Henry, who liked to carry a bookbag and wear a scarf. After Emerson, Henry wound up going to Yale and coming out to Los Angeles.

One year, on his birthday, Henry was in an audition and he was asked to go into the restroom of a diner, look in the mirror and comb his hair. Henry said, “I’m going to go into the bathroom, I’m going to look in the mirror and I’m going to go, ‘Ayyy’” — that’s Henry Winkler’s character of the Fonz. That’s how it was born.

Q: So you were friends from your college days?

A: I remember sitting at a restaurant with him on Sunset Boulevard [when he was appearing on Happy Days]. He said, “Vin, I’m starting to get more letters than Ron Howard. I don’t know what this is going to be, but I think it's going to be great.” The rest was history.

He’s the most respectful, wonderful, caring — he’s just an amazing man. Always will be.

Part of the story he tells is, “Never take no for an answer.” The dynamics of never taking no for an answer are: be damn sure you're right, then go ahead and do it. But if you have a question about whether you're right or wrong, then you need to think it out because you could look pretty foolish.

But if in your heart and in your gut, you think you're right — which is the way I like to do television — go for it.

Q: You pursued radio at Emerson, then came to UCLA for graduate school….

A: I loved radio, and I was pretty good at it. I have a decent sense of humor, and I really liked spinning records. In the second year, I took television.

My first exercise was putting together a 30-second live commercial: fade up from black, go to a camera card, change the card, have music and an announcer and then you fade out. Scared the bejesus out of me. I was so nervous. Then we did a second one.

I practiced being a director, rolling the cues and all of that, in front of a mirror for about an hour. When it came time to do the assignment, I nailed it. Then it was like starting to eat a huge bowl of peanuts — I just couldn’t stop.

Q: How did you and and Henry Winkler end up working on MacGyver together?

A: Henry and I had wanted to work together for a while. One day he said, “I’m going to send over a script. Read it and tell me what you think.” It was Saturday afternoon, and it was the MacGyver pilot. I said, “Henry, this is amazing!”

He said, “Well, you've got to get approved by two guys at Paramount. One is heading syndication and production; his name is John Pike.” I said, “That shouldn’t be a problem. John was my executive producer at WBZ for years. He gave me my going-away party.”

But I had just been offered a job to do two specials at $50,000 each. I had been out of work for a couple of months. Henry said, “They won’t be able to make a decision until Tuesday, after they meet you.” I said, “But Henry, I’ve got an offer on the table. I have to tell them by Monday.” He said, “Well, Tuesday’s the earliest.”

I had to tell my wife that I was going to pass up $100,000 of work on a maybe from the guys at ABC. But I took the shot and I passed on the job. About four hours later I got the call from Henry. He said, “You got approved.”

Q: What was the biggest challenge in getting that show off the ground?

A: We had to figure out who MacGyver was. We started the auditions, and the first guy through the door was Richard Dean Anderson. He left the room and we said, “That’s MacGyver. He’s the first guy through the door — this can’t possibly be right.”

We went through 60 other people, and sure enough, Ricky was the guy. Came in with a bombardier jacket on and khakis — I think he had the Swiss Army knife with him, too. Great fun. I was line-producing and second-unit directing and having a ball.

Q: When did you start Vin Di Bona Productions?

A: I was watching the late news, and there was this story about an Australian frilled lizard that was taking over Tokyo. People had started importing them, and the little suckers were running all over the streets in Tokyo.

At the same time there was a game show called Waku Waku Animal Land, and it had done pieces all over the world about unusual animals. They had an episode about this lizard and I saw a clip. I wanted to find out who owned the show.

Q: And that’s how you started?

A: It took me about six months to find out that it was Tokyo Broadcasting. I called them and said, “I’d really like to bring your show here.” It was basically Wild Kingdom meets Hollywood Squares. They had all this great footage, mostly about what animals would do to get food. The footage included documentary pieces about animals, their habitats and their families.

[In the game show] the celebrities would guess what an animal would do next. I got a tape from Tokyo, and I used it to make a 12-minute reel. I took it around, and everybody would laugh out loud because it was hysterically funny. Then they’d say, “But it's Japanese.”

I’d say, “Well, imagine if that celebrity is Betty White or Zsa Zsa Gabor. They still couldn’t get it. I pitched it 136 times.

Q: So, what happened?

A: On a lark, my old buddy Squire Rushnell from WBZ, said, “I’m looking for something for Saturday mornings. We’re taking American Bandstand off the air, and we need a show that women 18 to 34 would like to watch.”

I sent him the reel that I’d put together. He called back the next day. That’s how Animal Crack-Ups started. We were the first U.S. company to bring a Japanese show to the U.S. That went a long way in Tokyo, and it still does.

Q: What was the original premise for America’s Funniest Home Videos and what was your pitch?

A: In the third year of Animal Crack-ups, we’d pretty much run out of footage from Tokyo. The Japanese came over and showed me these home videos, and they were hysterical! I went over to the Tokyo Broadcasting booth at MIP, and there was a line of at least 150 producers trying to get in to look at these clips.

Because of my prior work with them, they ushered me straight in. We talked about the ability to bring the show to America, but it was a variety show and in 1988–89, variety was gone.

Q: What was their format?

A: It was comedy sketch. The Japanese version was called Fun TV with Kato-chan and Ken-chan, who were two stand-up comics. It involved some dancing segments, a music segment, a little bit of talk and then a home video. They repeated that cycle three times in one show and at the end of the show, the four or five celebrities picked one of the three videos [as the winner].

They said, “What do you think?” I said, “The videos are amazing, but that format’s never going to work. I think we should just run all home videos and pick a winner at the end.”

Q: And they agreed?

A: An interesting thing happened. While I was at the Tokyo Broadcasting cocktail party that same night, I saw a producer I had worked with at KNXT. She was there representing another variety producer.

She said, “I’m here scouting, and I hear this home-video idea is pretty terrific. I’m going to talk to the Japanese tonight.” I said, “Oh, that’s really great. Would you excuse me for a second?” I walked over to the Tokyo Broadcasting booth and said, “We need to make this deal right now,” and we did. That was it.

Q: What kind of video submissions are most common?

A: Dogs and kids. And weddings.

Q: How many submissions are you getting now, versus back in 1989?

A: In the first six months the Hollywood post office had to bring in three extra employees just to handle our mail. We would get upwards of 36 mailbags a week. We had three shifts of screeners.

As the show started to go mainstream, we would get about 700 or 800 clips a week in the snail mail. Now we get between 3,500 and 5,000 videos a week that are uploaded.

Q: What are the rules regarding what videos can and can’t show?

A: [We don’t air videos that involve] bad parenting, if it's harmful or if it's in very bad taste. Vomiting, we consider good taste. Crotch hits, we consider extremely good taste.

Q: Why is that?

A: I’m going to tell you a story. We started selling the show to Europe, and the Dutch said, “We can’t put your show on the air.” I said, “Why?” They said, “Well, people laughing at someone having ill fortune is a social disgrace in Holland. So if someone gets hit in the groin, we feel very sorry for that person.”

The show did go on the air, and there was a crotch hit in the opening salvo. It was like everybody in Holland watched and laughed at the same time. It’s never been a problem since.

Q: What about the studio audience? Have they been prepped about the clips they’ll be seeing?

A: Not at all. We cater to them. We interview them and we put them on social networks. We have a big cut-out of [host] Tom Bergeron [who stepped down after season 25 and has been replaced by Alfonso Ribeiro]; we take pictures of them with Tom and put that on social networking.

But I’ve done something with the audience since day one. What bothered me so much in variety shows and in audience-participation shows was people who would show up in shorts and flip-flops, chewing gum. So I don’t allow any of that.

How do we get people to dress up? We offer a $100 award for the best-dressed man and best-dressed woman in the show.

Q: And you get some pretty crazy outfits….

A: We get tuxes with tails. We get everything.

Q: The AFV collection is being added to the Smithsonian. What does that mean to you?

A: It was such a thrill. I’ve peripherally seen the experience as it happened to Henry Winkler with his Happy Days jacket. Ours is not in that same echelon, but to be there and be part of television history — I’m very proud of that. And really proud of the people who do that with me.

We have a really great crew. Often we’ll have a family picnic in the summer, and I can see the families that have grown up on this show. People have bought houses, had children, got married while working on the show. It's a good feeling.

Q: Do you have a favorite clip?

A: I always say my favorite clip is the next clip that comes in and makes me laugh loudest. But there are two that I love.

One is of a kindergarten class, and all the kids are dressed in cap and gown. The teacher asks each kid to come up to the microphone and say what they want to be when they grow up. So the first kid comes up and says, “I want to be a vampire bat,” and the teacher says, “Okay, you want to be a vampire bat.”

Next kid comes up, the third or fourth kid comes up and the teacher says, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” And he says, “I don’t want to grow up.”

Second clip: a mother and father are showing their three-year-old daughter numbers on flashcards. They hold up the number five and she says, “Five.” They hold up the number seven and she says, “Seven.” They hold up the number eleven and she says, “Pause.”

Q: What advice would you give an aspiring TV producer?

A: Don’t worry about money. With success, that will come. Be kind. Be a team player. But know when not to be a team player and make a decision, because you have to do that. Every once in a while it's good to be king, because that will get a project done with your vision.

Treat your friends well and try to pay more attention to your family. I don’t think I did that enough, as much as I love everybody.

Build a really good team of people you can trust and rely on, and make them know that you really care about them and their vision. But it’s always got to be your vision. Have patience, don’t get excited and don’t scream. This is about as angry as I ever get, and people like that.