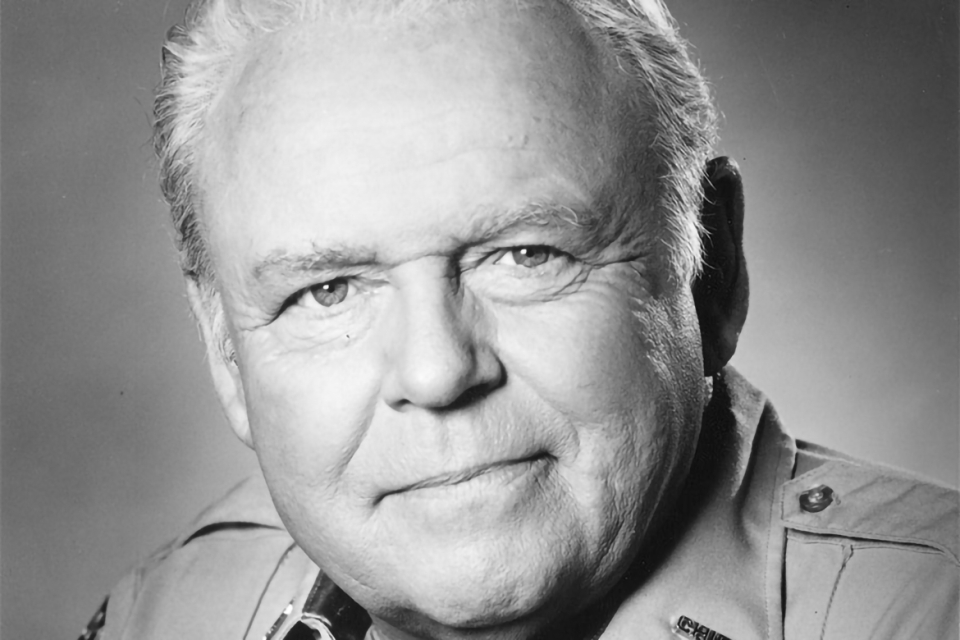

As Archie Bunker on Norman Lear’s groundbreaking series All in the Family, Carroll O’Connor played a thickheaded bigot — perhaps television’s most renowned.

But in real life O’Connor was man of letters, attending university in Ireland and earning degrees in history and English literature. He yearned to be a writer.

“I used to read the Saturday Evening Post and dream about being one of those writers,” the late actor said.

He also loved the movies, but never envisioned himself as a performer. “That seemed so far removed from me,” he said. “I couldn’t even go there in my imagination because it was a glamour world — and I didn’t think of myself being in this glamour world.”

John Carroll O’Connor of Bronx, New York, was certainly not born into glamour. The son of a criminal lawyer and a retired teacher, he tried to enlist at 18 in the Naval Air Corps — the year was 1942 — but he was rejected for physical reasons. He later joined the National Maritime Union and served as a purser during World War II.

After the war, he accompanied his brother Hugh to Dublin, and the change of scenery changed his life. He attended Ireland’s National University and, after performing in plays there, was hired to perform professionally on stage. Yet it wouldn’t be until he returned to New York that his career would eventually take off with numerous roles in American television.

In 1968, three years before the premiere of All in the Family, he was cast as Archie Bunker. The role would earn him four Emmy Awards (he later received a fifth for his performance as Chief Bill Gillespie in the NBC series In The Heat of the Night).

O’Connor, who died June 21, 2001, at 76, was interviewed in 1999 by Charles Davis for the Television Academy Foundation’s Archive of American Television. An edited excerpt of that discussion follows; the full interview can be viewed at TelevisionAcademy.com/archive.

Q: What caused you to considering acting?

A: When I started at the University of Montana, there was a drama club on the campus. I took a theater history course and I appeared in several plays. I rather liked it. But I still wasn’t thinking in professional terms.

When I moved to Ireland, the university there did an extraordinary production of a T.S. Eliot play called A Cocktail Party. I was in it and I was very good. After that a producer invited me to be in a professional play. Just like that.

“I think you’re very talented,” she said. So I played a part in a play, and it was a thrill. All these very good Irish pros made me feel so welcome. I can’t tell you how happy it made me. I was hooked. My plans to be a historian, writer and teacher? Out the window.

Q: You did some television for the BBC, and then in 1954 you went back to New York….

A: Yes. Wished I hadn’t, though. I couldn’t get any work. I couldn’t get an agent. Everybody thought the world of me in Ireland and in England, but in my hometown I couldn’t even get in the door.

I was 30, so I took a job as a substitute teacher. Then I went back [to school] and got a master’s degree. I started doing off-Broadway work and did a television show [Sunday Showcase] in New York.

It was the story of the murder trial of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and I played the prosecutor.

Q: So, you moved to Hollywood in 1960 and soon you landed roles on a lot of popular shows — The Untouchables, Bonanza, The Fugitive…. How did All in the Family come about?

A: Another fellow had the property before Norman Lear, a young producer named Howard Adelman. He had bought it in London [where it aired as Till Death Us Do Part] and come over here with it.

He was talking to ABC, and somebody told him to sign me to play [the lead]. He did. One day he called and said that ABC wanted him to join forces with producers Bud Yorkin and Norman Lear — did I mind?

I said, “No, I don’t mind, as long as my deal goes on to these guys.” Nobody knew the hit it was going to become.

Q: What happened at your first meeting with Norman Lear?

A: Shortly after Howard Adelman made his deal with Norman, I was invited in to meet him. I went to his office on Sunset Boulevard. He was very cordial. He said he’d be sending me a script in a few days. So I left, and in a few days I got the script.

This was one time I thought, “I’m going to be very big in the collaboration on this.” He had talked with me about the character and so forth, and he said some people thought Archie should be from Texas, since he was a bigot.

I said, “No, no, make him a New York Cockney.” The guy in the English version was a London Cockney.

Q: You were very familiar with the British version….

A: Yes, and when I got the script for the American version, I thought it was terrible. I thought, “I’m going to rewrite this. If he doesn’t like it, then he can just get somebody else.”

I rewrote the script, all in pencil. Then, since I had no typist, I recorded it on tape, playing all the parts — Edith, the Meathead, Archie, the black kid from next door. I brought that tape in and gave it to Norman. It was a complete rewrite.

He played the tape and then gave it to his secretary and said, “Transcribe this.” She made a script out of it. And that’s the script we did for the pilot.

Q: An amazing turn of events….

A: Yes. Norman never told the story… for years. Finally, when the two of us were on The Mike Douglas Show, Mike said something about the show’s superb writing. And Norman said, “The best writer this show ever had was this fellow right here,” pointing to me. Which surprised me, because Norman was never great for sharing credits. Then he told the story I just told you.

When the show was over, I said to the Mike Douglas people, “This is a tape I must have. I must have this evidence.” They gave it to me.

For some reason, Norman felt moved that day to tell that story. Over the years that we’ve worked together, he seemed very anxious to keep my name out as a writer, although I rewrote shows every week.

In fairness to him, it may have been that his team of writers would’ve objected. On the other hand, if the writers had objected, let them object.

Q: What was your approach as you developed Archie?

A: Archie, like his counterpart in England, was a dumbbell. He didn’t know why he was conservative. Had no idea.

I knew why Archie tended to move toward conservatives. He thought that they would keep the country racially pure — or close to pure. And that was stupid, because the country is not racially pure.

He had his inbred dislike and distrust of blacks. He didn’t dislike Jews, but he didn’t trust them. As he said to Edith, “If you get a cold, you can go to anybody. But if you get something serious, you got to get a Jew doctor every time — or a Jew lawyer.”

Q: What was your take on Archie’s ideas?

A: All his preconceptions were keeping him from enjoying life. That was my message. Archie never enjoyed anything. He never smiled, never had anything nice to say about the day. Something was always poisoning life for him.

He didn’t realize that his father had passed it on to him. We finally got to the point where I wrote these things in.

I played a scene with Rob Reiner in which Archie was drunk and talked about his upbringing. He didn’t tell it as if he were confessing a horrible thing: “When your father tells you these things, that’s the guy who’s taught you how to play ball, took you for your first walk, held your hand. This is the father who loves you, and he ain’t going to lie to you.”

It came from Archie’s heritage.

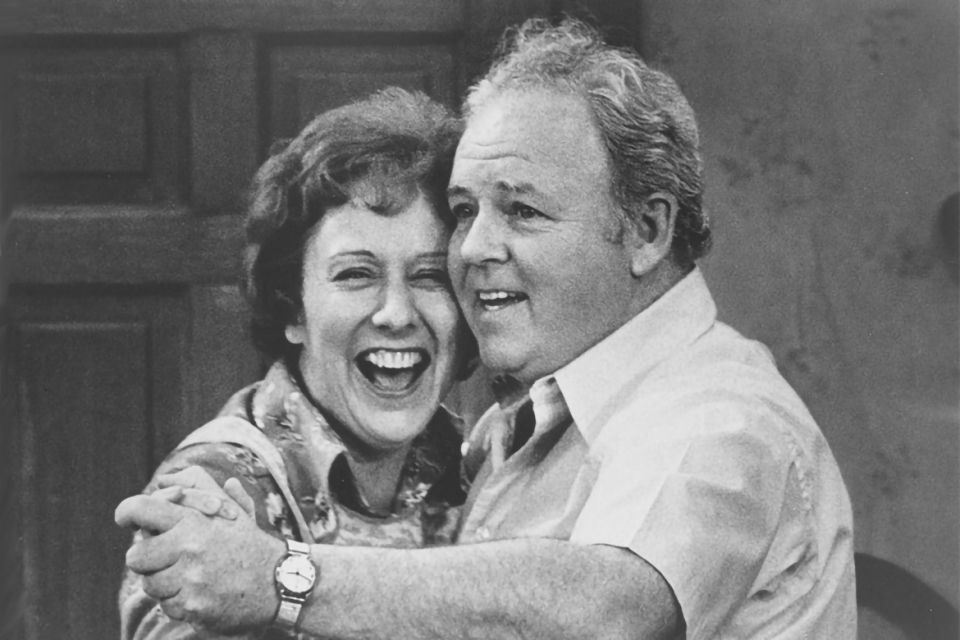

Q: What was it like working with Jean Stapleton?

A: Working with Jean was one of the great pleasures of my life. I think Jean made All in the Family. She was exactly the right counterpoint for Archie Bunker. And her character was all-important.

She represented not the target of all of his remarks, but the proper reaction. She was the sensible, moral reaction to this nonsensical, immoral man.

Q: Before the show aired, you shot three pilots….

A: We shot the first pilot in a New York theater with an audience. The audience howled that night. But ABC owned the show [at that point] and wanted to do it again with two other actors to play the kids.

So when I came back from a trip to Europe, we taped a second pilot at the ABC studios with another boy and girl. The executives at ABC rejected that, too. So, I forgot about it.

I went to Europe and was there for more than a year when I got the call: Norman had sold the show. He’d got it back from ABC and sold it to CBS.

Q: What are your memories of filming that first episode?

A: We did it at CBS. Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers had been hired. We did the same script as we had done for the first and second pilot. By that time, we knew where all the laughs were, and there was no sense in changing any of the [dialogue].

Q: How did your colleagues respond to your performance as Archie?

A: They all liked the performance very much. But one fellow objected to the show. He was a writer and asked me to have lunch with him in the CBS commissary. He said, “I’m surprised that you would do a show like this with your overall reputation as being a liberal man. I’m really shocked at you.”

I said: “Well, don’t you get it? We’re kidding the character.”

He said: “I understand, but that’s not what’s happening.”

I said: “Yes, we’re making a fool out of Archie Bunker. That’s how we are going to repay his racism and his bigotry.”

He said: “You may think that’s what you’re doing, but you’re really playing to a crowd of people out there who are indeed Archie Bunker.”

Q: Did you think he had a point?

A: Well, it turned out to be true. But the other thing turned out to be true, also. We did make a fool out of Archie, and everybody saw him being made a fool.

But there were many people who thought Archie was 100 percent right about everything. I don’t know what percentage of America — and I’d like to think not a large percentage — but I’m a little bit afraid it was.

Q: In 1974 you walked off All in the Family and filed a lawsuit….

A: The suit was just to cover myself from walking off. My original contract called for me to be in an executive capacity, whatever the billing. I would have script control, and I would be a writer on the show.

I also wanted $25,000 an episode. I got the money, but I didn’t get the other stuff. That’s all right. The show went on. There were several battles over money.

Q: Let’s talk about some classic All in the Family storylines, starting with Edith’s menopause….

A: That one became famous for Archie’s line: “Now, I’ve had enough of this. If you’re going to change, Edith, change now.”

Q: There was the episode about Gloria’s miscarriage….

A: That was one of the earliest shows. That was very tragic. And that established Archie as a guy with real sentiment, a real heart and real love for his children.

Q: There was the death of Beverly LaSalle (played by Lori Shannon), the transvestite that Archie had saved when he performed CPR on her.

A: Archie was appalled at what he had done, giving this [female impersonator] mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. But he felt bad when he heard that she or he had been in an accident. It showed the other side of Archie a little bit.

Most of these shows did that. We threw light into another corner of his character on many occasions.

Q: There was also the episode in which Sammy Davis, Jr., came to visit….

A: That was a very successful episode. It wasn’t a likely story [Davis’s character leaves a briefcase in Archie’s cab]. Sammy had said he wanted to be on the show, and this was how we got him on. It was a show with mostly gags and jokes. It wasn’t applicable to anything.

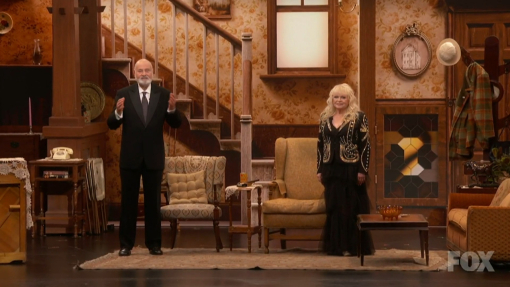

Q: At the end of the ninth season, All in the Family became Archie Bunker’s Place. How did that come about?

A: The show was over. Jean Stapleton had given notice that she would not come back. The young people didn’t want to come back. Neither did I. I’d had enough — we’d all had enough. Robert Daly, the president of CBS, came to me and said, “I’ve got to have that show, Carroll.”

I said: “You expect me to do it alone? Who is with me?”

He said: “I don’t know. We’ll try this one way or another. I’ve got to have that show.”

Q: What happened?

A: He went to Norman Lear, and Lear said no. He wanted the show to die an honorable death. In another day or so, Bob Daly called me again. “Carroll, will you go and see Norman? He’ll let us do this if you ask him.” I said, “Okay.”

To make a long story short, Norman said we could do it. But we couldn’t call it All in the Family. We couldn’t use the opening song with Edith and me. And we’d have to keep Edith alive as a character, even though she wasn’t seen. I said, “How do you do that?”

Norman said: “You’re in a bar a lot, and she’s at home. We don’t cut to her. Or she is on a long visit with the relatives.”

And I said, “Norman, that’s crippling the show. I think Edith must die.”

“No, no, no,” he said. “I don’t want that.”

Negotiations broke down. I told Bob Daly what I had told Norman. He said, “Jeez, I wish you hadn’t said that.”

I said: “Well, talk to Norman and tell him I can’t do this show with a nonexistent Edith. We’ll have to write a show in which she dies and then go on without her.”

Q: What did you want to do with the character arc?

A: I brought Martin Balsam in from New York to play a Jewish guy who had bought this partnership in the bar. He becomes Archie’s partner.

The object was to bring Archie closer to the Jewish way of things, to show him that, in many ways, it was his way, too. It’s everybody’s way. That he was distrusting these people for no good reason.

His partner was a wonderful fellow. The partner got to like him. It was supposed to, in plain words, teach Archie Bunker about Jews.

Q: In 1988 you became the star and executive producer of In the Heat of the Night (a TV spinoff of the 1967 film starring Rod Steiger and Sidney Poitier). How did that come about?

A: Lynn Loring, who was then vice-president of television at MGM, said to [producer and former ABC and NBC president] Fred Silverman, “I think In the Heat of the Night would make a good series. I’d like to see you produce it for us, and I’d like you to get Carroll O’Connor to play the chief.”

Fred came to see me — we had lunch at my restaurant. He said: “What do you think?”

I said: “Yeah, it could make a good series.”

He said: “If you tell me today that you’ll do it, I‘ll have a deal with NBC in two weeks.”

I said: “Okay, Fred, I’ll do it.” He had the deal in two weeks.

Q: You had some health complications while on the show….

A: My arteries were blocked. I had [sextuple coronary bypass surgery] and I missed about four shows. They got through the season — they brought in some guy who was filling in for the chief.

But they couldn’t have the chief out having heart surgery. They had to make up some hokey-pokey stuff about his being kidnapped, and there was some voodoo mixed in.

Q: What is your best advice for a young actor starting out in television?

A: I tell every young person to stay with it — even if it takes 10 years — if he’s sure that he can be a good, important actor. I was an important actor because all the producers in town knew that if they got me I would help their picture.

When you achieve that reputation, you are important — maybe even more important than some of the stars. We should all try to be important fellows in our industry. Don’t give up. It will happen. Then, when it happens, bingo! You’re on top of the world.