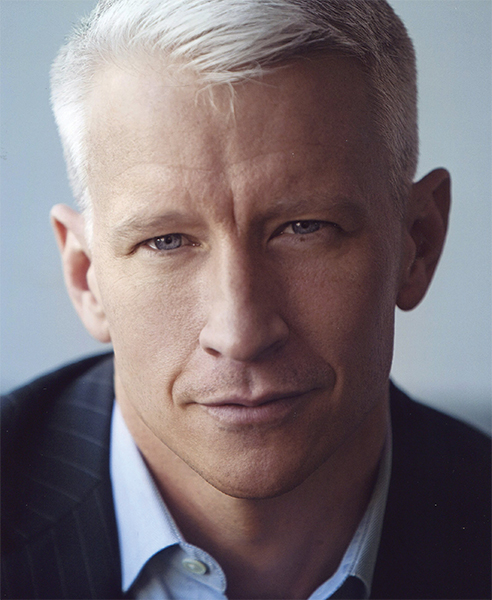

Fame has always played a part in the life of newsman Anderson Hays Cooper.

The son of Gloria Vanderbilt and kin to a long line of Vanderbilt railroad magnates dating back to Cornelius Vanderbilt — the 19th-century businessman named one of the richest men in America — Cooper grew up in a rarefied world.

Acclaimed photographer Diane Arbus shot him as a baby and, by the time he was in grade school, he was appearing on the game show To Tell the Truth. But tragic events would ultimately shape his life in ways he could not have imagined as a child.

When his father, author and screenwriter Wyatt Cooper, died suddenly of a heart attack at 50, young Cooper was devastated.

“I realized nothing is guaranteed, and I started feeling like I needed to be independent in all ways,” says Cooper, who would then work as a child model for three years. “I became obsessed with the idea of earning my own money.”

As a teen, Cooper took several outdoor survival courses and left high school early in his senior year for a months-long overland trip across southern Africa, observing lives in such far-flung regions as Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and spending days with Mbuti pygmies.

“That trip made me realize this was something I wanted to do,” Cooper says. “It felt much more real to me than my life in New York. It definitely had an impact on the kind of reporting I would do later and the kind of things that I did as an adult.”

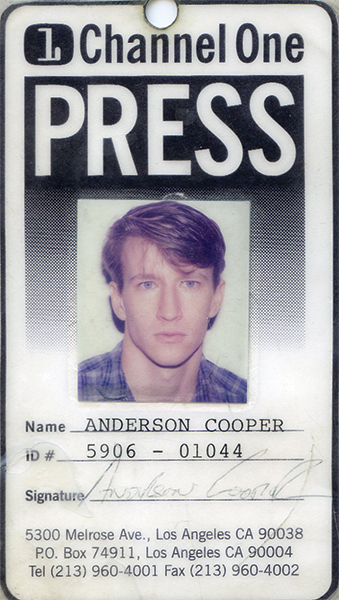

He started his reporting career at Channel One, a digital news service for students, and eventually made his way to some of the most prestigious reporting jobs in television, including his current positions as anchor of CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360˚ and as a contributor to CBS’s 60 Minutes.

Cooper was interviewed in December 2014 by Jenni Matz for the Television Academy Foundation’s Archive of American Television. An edited excerpt of that discussion follows; to view the entire interview, please visit TelevisionAcademy.com/archive.

Q: You lost your father at a young age….

A: Yeah, my dad died when I was 10 and that obviously changed everything. I became a much more independent person after that, but I also became a less interesting person. I think the person I was before I was 10 was much more interesting than the person I am now.

There’s a saying by a writer, Mary Gordon, who was talking about girls, but she said, “A fatherless girl thinks all things are possible and nothing is safe.”

I think the same applies for fatherless boys. It opens up a world of possibilities, both good and bad, and it also makes nothing feel safe again.

Q: What were some of your interests as a kid?

A: I started doing survival stuff when I was a teenager with a group called NOLS, the National Outdoor Leadership School. That was really a reaction to my dad dying, just wanting to be independent and wanting to prepare myself for any eventuality. I wanted to know that I could survive in the wilderness, even though I was growing up New York City.

I did a mountaineering course in Wyoming for a month. I did a sea-kayaking course in Mexico for a month.

By my senior year in high school I’d already completed whatever requirements were necessary, so I came up with this scheme of finding something really interesting to do and seeing if I could convince my high school to let me go, and I did.

Q: What was that?

A: I found a magazine ad for overland trips across Africa. These companies used to supply an old British Army lorry and you could ride from South Africa all the way to London for about six months or a year, so I signed up.

It really opened my eyes. It was the first time I’d had a gun pointed at me. It was the first time I’d been yanked out of a vehicle and had soldiers line us up on the side of the road and make threats. It was the first time I’d seen completely different cultures.

I’d traveled a little bit in Europe, but each of the countries we traveled to in Africa was so different and so varied. I found it fascinating.

Africa really quickened my pulse and shaped my eye and changed the way I saw things. That trip made me realize this was something I wanted to do. It felt much more real to me than my life in New York.

It definitely had an impact on the kind of reporting I would do later and the kind of things that I did as an adult.

Q: What did you do after college?

A: My brother [Carter, then 23] committed suicide right before my senior year, so senior year was kind of a blur for me. I didn’t really prepare for graduation. I didn’t apply for jobs. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I just wasn’t focused.

When I graduated, I had no plans. I decided to take a year off and travel around. I worked some odd jobs, like carpentry. I spent four months traveling around Southeast Asia with a friend.

I ended up making this list of everything I wanted from a career, and it all pointed toward being a correspondent: the traveling, creativity, writing, witnessing world events.

I liked the idea of being able to move around and see a variety of things and be on the breaking wave of history, see it firsthand.

Q: How did you then become a correspondent for Channel One?

A: I got hired as a fact checker at Channel One for six months, and that was about as much time as I needed to realize that I didn’t really want to be a fact checker and how much cooler it would be to be the correspondent.

But to get the job of correspondent involved a scheme on my part. I realized that once you're in a company, the people in charge only see you in one way and it's very hard to change that. If they see you as a fact checker, it's virtually impossible to convince them you’d be capable of being an on-air correspondent.

Q: So what was your scheme?

A: I had to make it virtually impossible for Channel One not to give me a shot as a correspondent.

I thought, “I just have to go to really dangerous places where other people don’t want to go to — or are too scared to go to — and I have to get some really compelling stories and show them to Channel One.”

I went to my boss and said, “I’m quitting. I’m going to go to Burma and hook up with some students who are fighting the Burmese government. It's going to be compelling because I’ll focus on young people. I’ll tell the story of kids in the jungles who are fighting this government. I’ll be on the front lines with them and, if you want, I’ll show you the story. If you like it, you can air it for $1,000.”

So they were like, “Sure, fine. We think what you're doing is ridiculous. You're not going to be a correspondent.”

Q: And you followed through?

A: I snuck into Burma, made a fake press pass and hooked up with some students fighting the Burmese government. My first day there I knew this was what I wanted to do.

There’s a saying my mom always said to me from Joseph Campbell, who was a professor at Sarah Lawrence, which is, “Follow your bliss.” It always annoyed me because I had no idea what my bliss was. But I realized there that I had sort of found my bliss.

There was something about being in a combat zone — it was so real. People look you in the eye and shake your hand hard, and I liked that environment. I didn’t want to live in it, but I understood the sense of loss.

I think when you lose a parent — or in my case, a parent and a sibling early on — I felt like I spoke the language of loss and I understood it. I was comfortable in an environment where life or death was very much in the air.

I was very much interested in survival and why some people survive and other people don’t. I shot a story in Burma and Channel One aired it.

Q: You’ve traveled all over the world and been witness to terrible tragedy….

A: There is no magic way to deal with seeing the suffering of others. I think it should keep you up at night. It should make you cry and it should change who you are. It should always do that.

It does that now for me just as much as it did 20 years ago.

Q: Among the many stories you’ve covered was the devastating famine in Somalia. How do you cope with what’s happening right in front of you?

A: I felt privileged to be there. I felt like, “This isn’t about me. This is about these people who are suffering, and I’m privileged to be here and bear witness. I’m privileged to be able to give them a voice and learn their names and at least know a little bit about them.”

I learned that tragedies happen all the time. But to me there’s nothing sadder than a person who’s lived a good and decent life, who’s dying on the side of a road and nobody remembers their name. It's horrific.

While I could not stop that from happening, to at least bear witness to it and not let it go unnoticed… that’s how I dealt with it.

Q: How did you get 360 on CNN?

A: The only reason I got a show at CNN is because Connie Chung had an 8 p.m. show and she left. Paula Zahn had the time period from 7 to 8 p.m.

They wanted her to anchor the two-hour block and she wisely said, “I’m not anchoring for two hours.” So they turned to me — the schmuck who will work any hours, any day — and gave me this block from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. I was like, “Yeah, sure, I’ll fill in.”

I anchored this awful two-hour show called Behind the Headlines. It didn’t last long. Paula then was given the 8 p.m. slot and they were like, “Look, we’ll give this guy 7 p.m.” So I was given a show.

As it turned out, I was working so much on weekends and a lot of stuff started happening then. They started to see that I could actually do breaking news. I had no idea that I could do breaking news, but I liked it when the teleprompter was blank.

Q: What did you like about it?

A: When the teleprompter’s blank and there’s a live event that’s occurring over the course of, say, eight hours — and you create a coherent narrative from little bits of information coming in — that’s when it's most interesting.

Q: When you covered Hurricane Katrina in 2005, there was a conflict between what the government was saying and what you were seeing….

A: That was incredibly frustrating. You're out with a body recovery team that doesn’t have body bags and has no place to put our fellow citizens who had drowned in their living rooms.

Bodies were rotting in the streets, and politicians were thanking each other on television. It was one of those times where you feel like you're in the right place and you feel privileged to represent and give voice to people who don’t have a voice… who don’t have access to the political leaders who are not there.

Q: What moment stands out?

A: I interviewed Senator Mary Landrieu, and she started off the interview thanking the president about the government’s response. It stunned me.

I always try to be polite to everybody, but I was blown away by what she was saying. I felt she needed to know what was happening there. I had this exchange with her that clearly surprised her.

I had just seen this family dead in their home, and I thought it was infuriating to have politicians thanking each other. It seemed so wildly inappropriate and so disrespectful to what the people there were actually going through.

Q: You’ve been labeled by some as the “emo” anchor….

A: It's interesting because I think I’m one of the least emotional people around. I’m a WASP, so I push all my emotions deep down and have done so my entire life. I actually think I’m pretty reserved.

In cable news there are people expressing anger and fury and phony outrage every single night, yet they don’t get labeled as emotional.

But genuine emotions like pathos or sadness, that’s labeled an emotion. I think it's okay to be a human being and be a reporter, as long as it's real and not artificial.

Q: What is your philosophy in regard to your on-air persona?

A: There’s a doctor named Milton Tectonidis with Doctors Without Borders. He’s a guy I really respect. I worked with him in Niger in a child malnutrition crisis.

He works in an E.R. and sees children dying all the time. One of the things he always says to nurses is, “It's not your job to cry. You're not here to cry. It doesn’t help the mothers to see the nurse cry. If you want to cry, it's fine, but go outside and do it by yourself.”

I think it's kind of the same thing for reporters. You try not to do it on the air. No one really wants to see a grown man getting all teary-eyed.

But we’re broadcasting around the clock and in places where that’s a completely understandable response. I can count on one or two hands the times it's happened in 20 years, but I can honestly say it's always been very real.

Q: You’ve also experienced being the subject of news coverage….

A: I know what it's like to have a camera pointed at you in sorrow. When my brother killed himself, there were cameras waiting for us outside the funeral home where we were going to view his body for the first time.

It was a big local news story in New York, and I remember hating these camerapeople and hating these reporters for being there. It was before I was in the news business. I understood why they were doing it — it was their job — but to have a camera pointed at you at your worst possible time… I never wanted to be that person doing it.

That has informed everything about how I interact with people in the field and how I tell stories. To this day, it’s something I think about every time I’m in a place where I’m dealing with people who are grieving.

Q: After the earthquake in Haiti, you had an experience with a young boy who was in danger….

A: That was a unique situation. Some young guys had taken over the top of a building, and one kid took a cement block and tossed it into the crowd. It hit a little boy on the head and the crowd ran away.

Blood was gushing out of his head, his eyes were rolling back in his head and he collapsed on the ground. He tried to get up only to collapse again.

I was afraid they were going to throw another brick at this kid. I had my camera in my hand and I started to run toward him. My first instinct was to take video of it.

But I took two steps toward him and then I thought, “What am I doing? I’m going to videotape this kid while blood is gushing out of his head?” In a split second it just seemed inappropriate, so I grabbed him and put him under my arm and ran 50 or 60 feet to a barricade that had been set up.

I was trying to talk to him, but his eyes were still rolling back in his head and blood was gushing down his face and all over my arm. I put him over the barricade, and another passerby grabbed him and took him away.

Then I was faced with, “Do we incorporate this into the story?” I thought, “Well, if we don’t incorporate it, then it looks like I’m trying to hide something.” So we put it in the story.

Q: How do you deal with celebrity?

A: Honestly, talking about celebrity makes me incredibly uncomfortable. I don’t acknowledge it. It has no reality for me. I don’t think anything good comes from paying attention to it.

When people talk to me in the street, I have such a bad memory I have no idea if I actually know them or if they recognize me from TV. So I greet everybody with equal enthusiasm.

Q: What excites you most about what you do?

A: Not knowing on any given day what’s going to happen — and knowing that I can still go places. Even trying to document something from an anchor desk is still thrilling and incredible.

I can’t believe that this has all happened. I can’t believe that, considering how I started out with this idea of going to wars by myself — building a fake press pass and taking a hand-held camera — that I’ve actually been able to forge a life out of it. I’m very, very lucky.